John Sell Cotman

The Tertre Grisiere at Domfront, Normandy, from the Cent Etages Called 'Domfront from the Town'

c. 1820

| Artist: | John Sell Cotman, British, 1782 - 1842 |

| Title: | The Tertre Grisiere at Domfront, Normandy, from the Cent Etages Called 'Domfront from the Town' |

| Date: | c. 1820 |

| Object name: | Watercolour |

| Medium: | Graphite and sepia wash on wove paper |

| Support: | White, wove paper |

| Dimensions: | |

| Reference: | LEEAG.1938.0029.0030 |

| Credit Line: | Bequeathed by Sydney Decimus Kitson, 1938 |

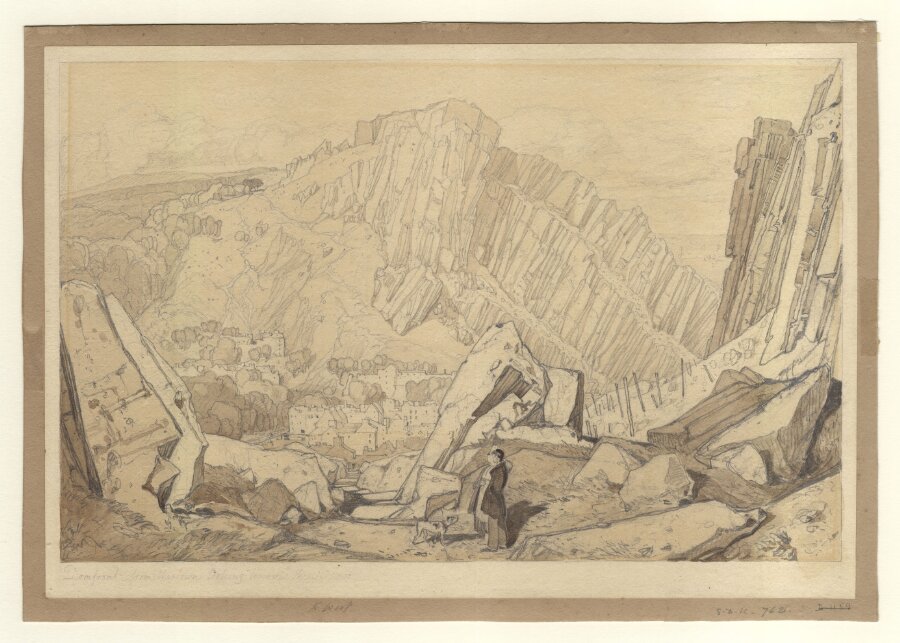

This is a careful graphite and sepia wash studio drawing of a rocky landscape, looking across a valley to a large triangular outcrop of rock from a flight of rocky steps descending past rocks at the base of cliffs to the right. In the foreground are two standing figures facing left, with a dog in front. In the middle distance left we can see the roofs of a small village, where a pedestrian bridge crosses a stream. As Kitson's 1937 list of his collection noted, the original mount has been inscribed by Cotman in graphite: 'Domfront from the Town looking towards the N West'.

Domfront is a picturesque small town in the rolling, wooded country of southern Normandy, a little over forty miles SSW of Caen and fifty miles east of Mont St Michel. Cotman visited the town only during his third and final tour of Normandy in 1820. On that occasion he made a tour from Alencon in the south-east of the region (see LEEAG.1949.0009.0819), working his way westwards to Domfront on 20 August 1820 (Letters II, p.113). Over the next four days he made a serious study of the town, and on the 24th an excursion to Juvigny and Bagnoles sur l'Orne (see LEEAG.1949.0009.0137) and on the 25th another excursion to Lonlay Abbaye, before travelling on to Mortain (see LEEAG.1949.0009.0095) eleven miles WNW on Saturday 26th.

Kitson's 1937 list notes that Cotman described the subject as 'Domfront from the Town'. This is slightly misleading, for whilst it is from that rough direction, the viewpoint is at some remove from the town proper. Domfront occupies a rocky ridge running east-west terminated to the west by a steep rocky valley where the Varenne river cuts a winding north-south course. The rocky valley supplied a fine defensive site for Domfront Castle and the town. Cotman's view is taken from the still-surviving 'Cent Etages', or 100 Steps, that descend into the rocky valley from the barbican. The rocky outcrop opposite is the distinctive Tertre Grisiere [also called by some sources the Tertre Sainte Anne] perfectly recognisable today albeit luxuriantly covered by trees. The hamlet at the lower left is that of Les Tanneries, and close inspection of the drawing will reveal a tiny footbridge crossing the river, which survives intact to this day. When I was there in September 2016 the whole descent of the Cent Etages was hemmed in by trees and overgrown hedges, and required serious pruning. The route seemed altogether under-utilised, and presented a decided hazard (as Mrs Hill can sorely testify) when descending. The stones were polished, many sloping downhill, and most covered in debris and grit. It would be very brave to attempt the descent in the wet!

Cotman's letters supply a wealth of colourful circumstantial detail. He stayed in the Hotel de Bretagne outside the walls and after initial doubts thoroughly enjoyed himself. He arrived on 20 August 1820 [Letters II, p.113 ff]: 'In the evening (Sunday) arrived at Domfront which appeared so unpromising that I dreaded even entering the Auberge, Public House, & remonstrated with my postilion & said he had not surely driven me to the best House, but he insisted that he had & that was enough, & he was right. - 'twas out of the town, for the town is so steep & narrow & wretched as to possess none - Notwithstanding appearance, the stairs having Mountains & Valleys of mud & filth upon them so as to be uneven to walk upon, got a good bed, clean linen, & excellent living, - Ducks, Chickens, &c every day for dinner & my bill at the end of 5 days, including the hire of a horse for one day only, 17 francs, vis 14-2d English money, but more of this by and bye - Next day 21st, looked about me & soon found plenty to do - a good old Church of N Dame, and Views of Town & Rocks extremely grand.. This day commenced with rain & thunder the whole of the day at distance. In the evening it was a grand storm, such a one as to add to the magnificence of the place & the flashes were so vivid & appeared so near that thinking my umbrella no protection but rather likely to be a conductor, I hastened to my Inn where I enjoyed it from my loop-hole of a window that commanded a grand view for 30 miles over the most woody country possible, one mass of forest - Tuesday, 22nd, heavy rain whole day so as to prevent my drawing though I made repeated attempts and began several - Wednesday, the ducks in high glory at 4 o'clock, tremendous rain more heavy than ever, though the night had been fine with much wind - Nay a hurricane, so as to blow down chimneys, logs & heavy masses continually falling, & glass, rattling to atoms everywhere, with the music of the sign of a hotel de Bretagne grating like the setting of a saw - it cleared up & I managed to do something between showers - The clearing up of the mist & passing clouds over the forest have an inexpressible beauty to the already most superb & fine situation.'

The night before his intended departure he encountered a splendid example of official pettifoggery. As was customary he presented his passport and credentials at the Mairie, but on the pretext that there had been some supposed conspiracy in Paris he was put under suspicion, together with his innkeeper, and in the middle of the night was arrested and marched before the bench between two gendarmes and held the night as a prisoner. He was released the next day after a local gentleman interceded on his behalf. He seems to have had greater cause for criticism than he expresses, and is careful in his letters not to make any imputations, except to say that his original bill of 17 francs for five days, which he thought eminently reasonable, more than doubled overnight to 39, with the addition of 'expenses for self & Host's process'.

Any separate on-the-spot sketches that Cotman might have made at Domfront have been lost. Rajnai 1975 pp. 65-8, under nos.22, 23 gives a survey of the surviving subjects and versions. Rajnai's principal subjects are two versions of the present composition at the Norwich Castle Museum (NWHCM : 1951.235.289 and NWHCM : 1951.235.702.B40). Both are studio sepia watercolours, and both close repetitions of the present composition. Rajnai says of the former: 'He was most impressed by it [the subject], loved it and paid pictorial homage to it. Not surprisingly it is one of his most successful Normandy drawings with such crisp and sensitive rendering of rocky scenery that it could hardly be bettered'. Of the second Rajnai says 'Whilst faithful in every detail, a confrontation with the original condemns it as a copy; neither the underlying drawing nor the laying of the wash compare in clarity with Cotman's drawing. The hand is, however, not of either of the Turner girls [ie. the daughters of Dawson Turner, Cotman's Yarmouth patron] and it is very close to Cotman's, so the attribution of Miles Edmund Cotman has a fair chance of proving to be correct.'

?

Of the Leeds version, Rajnai has faint praise 'An autograph version.. but with more prominent pencilwork.'. The Leeds version, however, is clearly the prime version of the composition, and in its delicate pencil work and sensitive use of wash sits perfectly in the main run of drawings that Cotman made for his 'Architectural Antiquities of Normandy' published in 1822. The essential difference between the Leeds and the Norwich versions is that the former is conceived primarily as a pencil drawing with wash, whereas the Norwich versions are conceived as sepia watercolours. It seems, however, that in the final selection of 100 plates, Cotman decided to concentrate on the architectural and antiquarian, and to slant his attention towards the academic in preference to the picturesque, and so his Domfront subjects were excluded. Finally, a little later in 1823, Cotman made a watercolour version of the composition for exhibition at the Norwich Society of Arts. Rajnai knew this only from a reproduction, but its exhibition from a private collection in the 'Cotman in Normandy' exhibition at Dulwich College in 2012 (no.30, where repr. colour) proved it to be an important work.

The present drawing makes a pair in terms of subject and style with a drawing of 'Domfront, Looking to the South East' at the USA, New Haven, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection (B1977.14.4695). This shows the view from the top of the rocky promontory of the Tertre Grisiere, the prominent outcrop in the Leeds drawing, but looking back across the valley to the castle and town. The viewpoint on the Cent Etages of the Leeds drawing is visible to the right of the centre. The Yale drawing likewise formed the basis of an 1823 watercolour at the London, Courtauld Institute Galleries, (D.1967.WS.22). Finally, the Norwich Castle Museum has a fine sepia watercolour that also shows the view of the Castle and Town from the top of the Tertre Grisiere, but from a viewpoint further back and to right (NWHCM : 1951.235.184).

Another subject at Domfront that Cotman specifically mentions in the letters is that of the old church of Notre Dame. This is the Romanesque church of Notre Dame sur l'Eau, which stands near the river Varenne a few hundred yards to the south-west of the town where the road to Vire crosses the river. This is known in a fine sepia watercolour now at the USA, New Haven, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1975.2.576, which once belonged to Sydney Kitson, and formed part of his bequest, but was subsequently allocated to the Royal Institute of British Architects, who sold it in 1975 to Paul Mellon and hence to the Yale collection.

Rajnai also mentions a pencil outline version of the view towards the town in a private collection but thought by Tim Wilcox in Dulwich 2012 (under nos. 29, 30) to be one of a pair of tracings of the Leeds and Yale compositions. Rajnai also mentions a sepia version of the Yale composition that was exhibited with Walker's Gallery in 1934, but is since untraced. He also lists several versions of a composition supposedly of Domfront showing a road leading over a barbican to a house overlooking distant country. Examples of this composition may be found in the Hickman Bacon collection (II/C/13) and at the Tate (T00972).

One incidental detail is worth particular consideration. In the foreground is a couple accompanied by a small dog. The dog appears to be a small breed of pointer. This might not be of any great significance except for the fact that Cotman's account of his stay in Domfront reveals that he was accompanied by his own dog on this trip. Speaking of the excursion to the Tour du Bonvouloir on 24 August, he says that, as they rode through the forest: 'My guide, for twould have been a vain attempt to have gone without one, was continually calling in my Dog & whistling to him, till he attracted my notice by it entirely, and I asked him why he did so. - He said twould cause his death if he met with a wolf.' A little later he describes a gentleman that he met on the road, accompanied by 'four large dogs, between the bull and the mastiff, certainly much larger & stronger than any I have ever seen - All the farm Houses have them'. The Yale drawing includes a man accompanied by two such large dogs, as a foil to the more modest animal in the present composition. It is tempting to see the smaller dog as a representation of Cotman's own.

In any case the evidence ought to provoke some consideration of how usual travelling with a dog might have been. What did he do with it at an inn? How did it travel when he went by diligence? What did he do with it when he visited a family in a chateau? Might this be the reason he was generally up very early, so as to be able to take it out? This is not the first time that I have been forced to consider such things. In 'Cotman in the North' (Yale University Press, 2005), it became clear that his dog at that time, called Tippoo, was both his companion and something of a liability. I was surprised at that time that Cotman could have thought it at all appropriate to impose a canine companion on his hosts and fellow travellers. Fifteen years later, his canine companion in Normandy must have been a different animal, but it is perhaps even more striking that he thought the trouble, and the imposition, worthwhile of taking a dog with him. This might prove an entertaining line of research for someone to develop further.

The contemporary visitor to Domfront might at first be puzzled by Cotman's picture. If one approaches the town as I did from the east, then the rockiness shown by Cotman reveals itself only slowly. If one parks at the entrance to the town, there is a cross on the south side of the square on top of an outcrop. After that, however, one has to make one's way through the town, past the church, across the barbican, into the castle grounds, and on to the very end of the peninsula, before the rocky valley of the river Varennes opens up, and even then because of the tree growth, it requires some perseverance to make it out. It is plain that the present composition is decidedly not of Domfront at all, but instead of its underlying geological structure. Once he had discovered these rocks, Cotman made great, and almost exclusive play of their form and fracture.

The Tertre Grisiere appears composed of three separate beds dipping steeply to the right at an angle of about 40 degrees. Each of these beds is splintered vertically almost like basaltic columns. In the foreground great shards lie strewn around. In truth the rocks of the Varennes ravine do not appear quite so distinct in form, but on consideration it becomes clear that Cotman does correctly highlight characteristic features of the structure. There are indeed three main beds as he shows, and these are indeed fractured through in the same general way although perhaps this is less obvious to the eye, confused as it to a considerable degree by surface staining. The rock also has a distinctively eruptive character where it breaks the surface. This is particularly evident around the remains of the castle. It is unclear what information Cotman might have had about the geology. Today we may understand that this stratum is called the 'Gres Amoricain' [see http://www.discip.ac-caen.fr/geologie/paleozoi/Domfront/Cluse.html] and consists of an Ordovician sandstone, metamorphosed at some remote time into a hard quartzite, outcropping at various places in Normandy, and creating rocky landscapes wherever rivers have cut through it. It is almost as if Cotman followed it systematically, for he drew subjects featuring it at Cherbourg (see LEEAG.1938.0029.0029), Mortain (see LEEAG.1949.0009.0095), Bagnoles sur l'Orne (see LEEAG.1949.0009.0137) and Falaise (see LEEAG.1949.0009.0758). A potential geological context for the composition was proposed by Tim Wilcox when he exhibited the Domfront watercolours in the 'Cotman in Normandy' exhibition at Dulwich College in 2012. Wilcox perhaps gives insufficient credit to the clarifying quality of Cotman's observations, but nonetheless observes that Dawson Turner had an interest in geology and the young Charles Lyell - later the greatest geologist of his age and author of 'Principles of Geology' published in 1830 - was a visitor to Turner's house in Yarmouth in 1817. Geology was perhaps the most rapidly emergent, controversial and popularly discussed scientific discipline of the early nineteenth century, and some of its propositions required a revision of the very foundations of understanding of the world. It seems eminently possible as Wilcox suggests, that Cotman was responding to a live and contemporary interest in the circles in which he moved, and had trained his eye in response to conversations in which he had participated.

Cotman would no doubt be pleased to discover that his work at Domfront is known there to this day. Following the signs for the 'Circuit Pittoresque', one comes at the foot of the Tertre Grisiere to an information board emblazoned with his watercolour of the site.

David Hill, June 2017

-

Provenance

?Hudson Gurney and by descent to Walter Gurney

Walter Gurney by whom sold at Sotheby's 19 April 1933

Sotheby's 19 April 1933, where bought by Squire's Gallery, London

Squire's Galley London from whom bt April 1933 by S.D.Kitson (1871 - 1937);

Sydney Decimus Kitson bequeathed to Leeds Art Gallery and accessioned 1938;

S.D. Kitson

-

Published References

H. Isherwood Kay (ed), 'John Sell Cotman's Letters from Normandy 1820' in The Walpole Society, 1927, Vol.15, p.113 ff;

Sydney Decimus Kitson, 'The Catalogue of the Collection of Drawings by J.S.Cotman', 1924-1937, unpublished typescript at Leeds Art Gallery, c.1937, cat.762;

Sydney Decimus Kitson, 'The Life of John Sell Cotman' (London: Faber & Faber, 1937) p.224, pl.98;

Victor Rienaecker, 'John Sell Cotman, 1782-1842' [Leigh-on-Sea: F. Lewis Publishers, 1953] pl.76;

Miklos Rajnai and Marjorie Allthorpe-Guyton, 'John Sell Cotman : Drawings of Normandy in Norwich Castle Museum' (Norwich: Norfolk Museums Service, 1975) p.68, under no.23;

'Leeds City Art Galleries: Concise Catalogue', (Leeds, Leeds City Council, 1976) cat. 29.29/38;

David Boswell and Corinne Miller, 'Cotmania and Mr Kitson' (Leeds: Leeds City Art Galleries, 1992) no.34;

Timothy Wilcox, 'Cotman in Normandy', (Dulwich: Dulwich Picture Gallery, 2012), p.82, under nos.29, 30;

Jean-Philippe Cormier, 'J.S.Cotman, Peintre de Domfront: une vue extraordinaire de Notre-Dame-sur-l'Eau avant sa destruction partielle', in Le Domfrontais Medieval, 2008-9, Vol.20, pp.4-22;

Jean-Philippe Cormier, 'J.S.Cotman, Peintre de Domfront: Nouvelles oeuvres 'domfrontaises', nouvelles versions', in Le Domfrontais Medieval, 2012-13, Vol.22, pp.21-34;

-

Exhibition History

Geneva, Le Musee Rath and Zurich, Le Cabinet des Estampes, 1955-6, 'L'Aquarelle Anglaise 1750-1850', no.27;

London, Agnew's, 1960, 'Watercolours and Drawings from the City Art Gallery, Leeds', no.96;

Munich, 1979, 'Zwei Jahrhunderte englische Malerei. Britische Kunst und Europa 1680 bis 1880', no.179

1991 'The Primacy of Drawing - An Artist's View' South Bank Centre, Bristol, Stoke, Sheffield (26)

Leeds, Leeds City Art Galleries, 1992, 25 November 1992-24 February 1993, 'Cotmania and Mr Kitson', no.34

-

Related Objects

Called 'View on the river Sarthe near Alencon', a lithograph by Vincent Brooks after a drawing by John Sell Cotman', Leeds Art Gallery, LEEAG.1949.0009.0819

'Recto: Crags near the Hotel des Thermes at Bagnoles de l'Orne, Normandy; Verso: Two sketches of a woman on horseback;', Leeds Art Gallery, LEEAG.1949.0009.0137;

'Recto: Two Woman Standing and a Man Seated; Verso: Part of a rocky landscape, possibly at Mortain, Normandy;', Leeds Art Gallery, LEEAG.1949.0009.0095;

'Cherbourg, Normandy, the Montagne du Roule from the banks of La Divette', Leeds Art Gallery, LEEAG.1938.0029.0029;

'Castle of Falaise from the south. Called 'Castle of Falaise/ North West View' ', Leeds Art Gallery, LEEAG.1949.0009.0758;

'Domfront, View from the Town', Norwich Castle Museum, NWHCM: 1951.235.289;

'Domfront, Normandy', Norwich Castle Museum, NWHCM: 1951.235.702.B40;

Domfront, Looking to the South East', Yale Center for British Art, B1977.14.4695;

'Domfront, Normandy, View of the town etc', Courtauld Institute Galleries, D.1967.WS.22;

'Domfront', Norwich Castle Museum, NWHCM: 1951.235.184;

'Notre Dame sur l'Eau, Domfront, Normandy', Yale Center for British Art, B1975.2.576;

[composition], Hickman Bacon Collection, II/C/13;

'The Ramparts, Domfront', Tate, T00972;

-

Collector's Notes

Sydney Decimus Kitson, 'The Catalogue of the Collection of Drawings by J.S.Cotman', 1924-1937, unpublished typescript at Leeds Art Gallery, c.1937, cat.762;

"DOMFRONT, from the Town looking towards

the N. West" (inscribed on original mount

in J.S.C's writing).

10 7/8" x 15 7/8"

Sepia.

from the coll: of Walter Gurney Esq., North

Runston Hall, King's Lynn (a descendant of Daniel

Gurney.)

sold at Sotheby's 19.4.'33 to Squire's Gallery,

whence I bought it 24.4.'33.

This drawing (which is squared faintly with 1"

squares) is similar to "Cleft Rocks" (10 3/4 x 16)

in the coll: of R.J.Colman. (photo.)

In the sale at Christie's May 1824 of Cotman's

drawings. 'Lot 109. A pair of highly interesting

views of the Town of Domfront and the Rocks in

the neighbourhood of same. In watercolours, not

pubd. 2.M. £5.19.0.

Cotman's Letters from Normandy. Walpole Soc:

vol: XV p.113.

"In the evening arrived at Domfront.........

Next day looked about me and soon found

plenty to do - a good old Ch. of N.

Dame, and views of Town and Rocks,

extremely grand"........ -

Alternate Numbers

Other number: 29.30/38

Previous Number: LEEAG.PA.1938.0029.0030

Negative Number: 791/1 (5)

Kitson Number: KITSON.762