John Sell Cotman

Mountain Landscape with Figures, possibly in Wales

c. 1835

| Artist: | John Sell Cotman, British, 1782 - 1842 |

| Title: | Mountain Landscape with Figures, possibly in Wales |

| Date: | c. 1835 |

| Object name: | Watercolour |

| Medium: | Graphite and watercolour on wove paper |

| Support: | White, wove paper |

| Dimensions: | |

| Reference: | LEEAG.PA.1924.0511 |

| Credit Line: | Bought with funds from the Alfred Bilborough Bequest, 1924 |

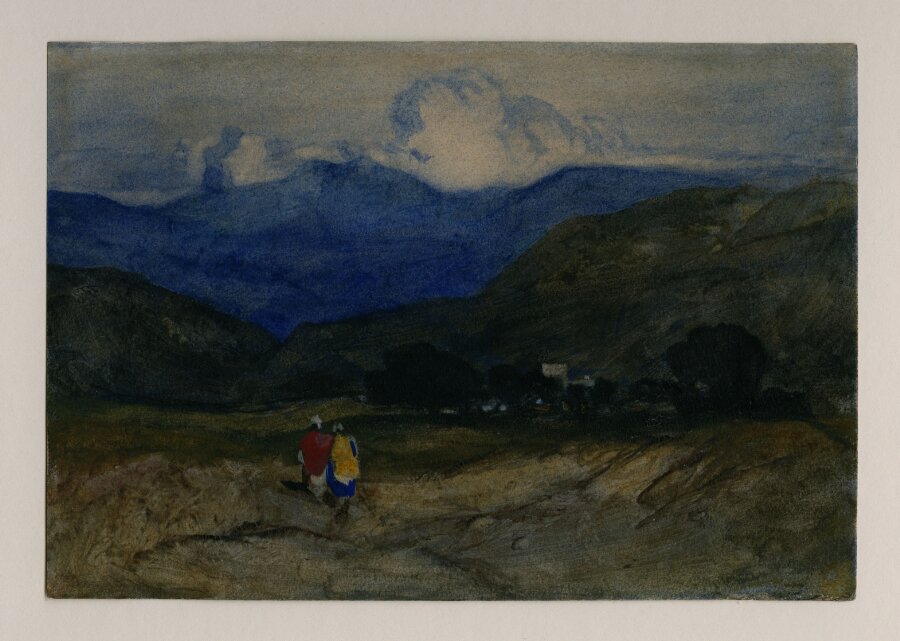

This is a small studio watercolour of a landscape composition of two figures walking along a wide valley towards a gap between low hills in the middle distance, with high blue summits beyond.

This is one of a distinct group of later watercolours painted in highly saturated colours mixed with a paste medium that Cotman adopted in the 1830s. All take landscape subjects, many, as here, apparently remembering his exploration of Wales at the outset of his career, reduced to poetic essentials. Around forty examples may be identified today. Some, for example watercolours of 'Cader Idris, North Wales' (London, British Museum, 1902,0514.26) and 'Mountain Landscape (Bedford, Cecil Higgins Art Gallery, Joll 2002 p.73 - once owned by Sydney Kitson) are even more sublimely essential than the present work. Others are more pastoral such as another example in the Leeds Collection, 'A Wooded Park' (Leeds Art Gallery 1939.0001.0011). Later examples eliminate colour altogether: Leeds has an example of that in 'Road to the Hills' (Leeds City Art Gallery 1939.0001.0003) and the British Museum has another, 'The shadowed stream' (1902,0514.57).

Leeds also has a pencil study of 'A lonely sea shore' that might be a rehearsal for a similarly reductive landscape composition (Leeds 1949.0009.0407).

The group was early identified as an aesthetic culminating point in Cotman's career. Solomon Kaines Smith reproduces the present work in the first full-length critical study of Cotman's work (1926, opp. p.126). In an account of the group he says (p.148) that it adds to Cotman's customary 'stern and sober simplicity of emphatic pattern, [and] the almost competitive appearance of pure colour' a third quality, 'no less sure in pattern, no less precise in its adjustment of complementaries. And intensely delicate recession of planes, and modification of colour, without the smallest sacrifice either of emphasis of design, or of opposition of colours.' He goes on to say of the group; 'These are in the latest and most experienced manner in which Cotman employed the colour devices of his earlier. method. . The point I am trying to bring out is that Cotman's art was, so to speak, cumulative rather than progressive, and that in turning over a page of the account he did not leave it behind but brought it forward to add to the sum of the next'.

Despite this early critical admiration, the group has not occasioned as much attention as it deserves, and for all that the present example is one of the major works in the Leeds collection, it seems to have been little studied or exhibited. Kitson does not mention it at all specifically in his 'Life of Cotman' and some commentators have even been ambivalent about the group. Miklos Rajnai in the catalogue of the Cotman Centenary exhibition commented on one, 'Rocky Landscape at Sunset' in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London: 'One of the late, highly alluring watercolours by Cotman spun from the basic constituents of landscape and having no topographic content whatsoever. This drawing and its companions are always a feast for the eye but, as they are not direct responses to particular visual and emotional experiences but constructions from elements provided by the artist's memory-bank, there is a somewhat disconcerting sameness about them.'

It has not previously been remarked that this group of late Cotmans is closely related to several late subjects by Cotman's life-long friend John Varley. His late work has a similarly 'visionary' character and might in turn be related to the later work of Samuel Palmer. All these artists transcend topography, but draw upon deep wells of experience as travelling artists. So whilst their minds dream of Elysium, their feet remember the trodden ground, and the depth of their work derives from that memory.

Almost nothing is known of the context in which such work was produced, although after Cotman moved to London in 1834 to take up his position as Master of Drawing at King's College School, he was an occasional participant in artist soirees. These involved such prominent watercolourists as John Frederick Lewis, George and Edward Cooke, James Stark, David Roberts and David Cox. The artists showed new work and work-in-progress and it seems possible that watercolours such as these found their first public in that setting. Cotman seems to have sold numbers of them too, although how such retiring, diffident and reductive performances were supposed to fare in the attention-demanding world of art exhibition at that time is uncertain. By the mid-1830s, however, it seems likely that Cotman had abandoned any expectation of general recognition, and consoled himself with his always high reputation amongst his fellow artists.

Together, the group demonstrates what a great achievement there is in Cotman's later work. Corinne Miller put its strength beautifully in her notes to 'Cotmania and Mr Kitson' at Leeds in 1992 (no.41). In a world which Cotman viewed as increasingly uncongenial and antipathetic, they were, she said, 'a harbour for the soul'.

David Hill, June 2017

-

Provenance

Purchased 1924 by Leeds City Art Galleries using funds from the Alfred Bilborough Bequest

-

Published References

Solomon C Kaines Smith, Cotman (London: Philip Allan & Co. Ltd, 1926) repr. opp. p.126;

OWCS club, vol XXXV 1960, p19 pl VIII

'Leeds City Art Galleries: Concise Catalogue', (Leeds, Leeds City Council, 1976) cat. 511/24;

David Boswell and Corinne Miller, 'Cotmania and Mr Kitson' [Leeds: Leeds City Art Galleries, 1992] p., no.40

-

Exhibition History

London, Agnew's, 1960, 'Watercolours and Drawings from the City Art Gallery, Leeds', no 88;

Paris, Petit Palais, 1972, 'La peinture romantique anglaise et les preraphaelities';

Leeds, Leeds City Art Galleries, 1992, 25 November 1992-24 February 1993, 'Cotmania and Mr Kitson', no.40;

-

Related Objects

A crossroads in a lightly wooded landscape, possibly at Whitlingham? Called 'A Wooded Park' ', Leeds Art Gallery, LEEAG.1939.0001.0011;

'Road to the Hills', Leeds City Art Gallery, LEEAG.1939.0001.0003;

'The shadowed stream', British Museum, 1902,0514.57;

'A lonely sea shore', Leeds Art Gallery, LEEAG.1949.009.0407;

-

Alternate Numbers

Other number: 511/24

Negative Number: 801/66 (12)