Cotmania. Vol. VII. 1931-2

Archive: SDK Sydney Decimus Kitson Archive

Reference Number: SDK/1/2/1/7

Page: 15 verso

-

Description

Lecture on English watercolour artists by Victor Rienaecker

A critical overview of English watercolour artists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Date: 1932

-

Transcription

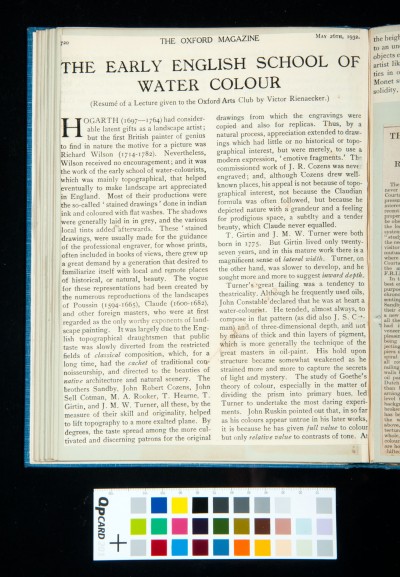

THE OXFORD MAGAZINE

THE EARLY ENGLISH SCHOOL OF WATER COLOUR

(Resumé of a Lecture given to the Oxford Arts Club by Victor Rienaecker.)HOGARTH (1697-1764) had considerable latent gifts as a landscape artist; but the first British painter of genius to find in nature the motive for a picture was Richard Wilson (1714-1782). Nevertheless, Wilson received no encouragement; and it was the work of the early school of water-colourists, which was mainly topographical, that helped eventually to make landscape art appreciated in England. Most of their productions were the so-called 'stained drawings' done in indian ink and coloured with flat washes. The shadows were generally laid in in grey, and the various local tints added afterwards. These 'stained drawings' were usually made for the guidance of the professional engraver, for whose prints, often included in books of views, there grew up a great demand by a generation that desired to familiarize itself with local and remote places of historical, or natural, beauty. The vogue for these representations had been created by the numerous reproductions of the landscapes of Poussin (1594-1665), Claude (1600-1682), and other foreign masters, who were at first regarded as the only worthy exponents of landscape painting. It was largely due to the English topographical draughtsmen that public taste was slowly diverted from the restricted fields of classical composition, which, for a long time, had the cachet of traditional connoisseurship, and directed to the beauties of native architecture and natural scenery. The brothers Sandby, John Robert Cozens, John Sell Cotman, M. A. Rooker, T. Hearne, T. Girtin, and J. M. W. Turner, all these, by the measure of their skill and originality, helped to lift topography to a more exalted plane. By degrees, the taste spread among the more cultivated and discerning patrons for the original drawings from which the engravings were copied and also for replicas. Thus, by a natural process, appreciation extended to drawings which had little or no historical or topographical interest, but were merely, to use a modern expression, 'emotive fragments.' The commissioned work of J. R. Cozens was never engraved; and, although Cozens drew well-known places, his appeal is not because of topographical interest, not because the Claudian formula was often followed, but because he depicted nature with a grandeur and a feeling for prodigious space, a subtlety and a tender beauty, which Claude never equalled.

T. Girtin and J. M. W. Turner were both born in 1775. But Girtin lived only twenty-seven years, and in this mature work there is a magnificent sense of lateral width. Turner, on the other hand, was slower to develop, and he sought more and more to suggest inward depth.

Turner's great failing was a tendency to theatricality. Although he frequently used oils, John Constable declared that he was at heart a water-colourist. He tended, almost always, to compose in flat pattern (as did also J. S. Cotman) and of three-dimensional depth, and not by means of thick and thin layers of pigment, which is more generally the technique of the great masters in oil-paint. His hold upon structure became somewhat weakened as he strained more and more to capture the secrets of light and mystery. The study of Goethe's theory of colour, especially in the matter of dividing the prism into primary hues, led Turner to undertake the most daring experiments. John Ruskin pointed out that, in so far as his colours appear untrue in his later works, it is because he has given full value to colour but only relative value to contrasts of tone. At