Cotmania. Vol. VII. 1931-2

Archive: SDK Sydney Decimus Kitson Archive

Reference Number: SDK/1/2/1/7

Page: 12 recto

-

Description

Kitson's diary entries 22 December 1931-11 January 1932; review of book by Clutton-Brock

Visit from Harold Isherwood Kay, who comments on the attribution and merits of works by John Sell Cotman and/or his son Miles Edmund; review of book on French painting by Alan Clutton-Brock

Date: 1932

-

Transcription

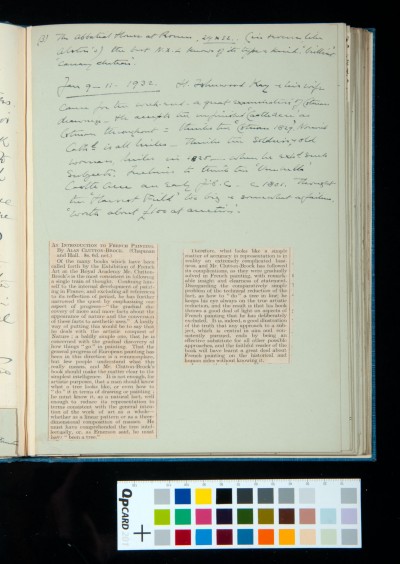

(3) The Abbatial House at Rouen, <24 x 32/. (in reverse, like Alston's) the best N.D.L. knows of its type & kind, 'brilliant', 'canary chateau'.

Jan 9-11, 1932. H. Isherwood Kay & his wife came for the week-end – a great examination of Cotman drawings. He accepts the unfinished ‘Castle Acre’ as Cotman throughout: thinks the ‘Cotman 1829’, Norwich Cath[edra]l is all Miles. Thinks the Soldiers, & old woman, Miles in 1825, when he exh[ibite]d such subjects. Inclines to think the ‘Umbrella’ Castle Acre an early J.S.C, c1801. Thought the ‘Harvest Field’ too big & somewhat a failure, ‘worth about £100 at auction’.

AN INTRODUCTION TO FRENCH PAINTING.

By ALAN CLUTTON-BROCK. (Chapman and Hall. 8s. 6d. net.)

Of the many books which have been called forth by the Exhibition of French Art at the Royal Academy Mr. Clutton- Brock's is the most consistent in following a single train of thought. Confining himself to the internal development of painting in France, and excluding all references to its reflection of period, he has further narrowed the quest by emphasizing one aspect of progress—"the gradual discovery of more and mure facts about the appearance of nature and the conversion of these facts to aesthetic uses." A lordly way of putting this would be to say that it deals with the artistic conquest of Nature; a baldly simple one, that he is concerned with the gradual discovery of how things "go" in painting. That the general progress of European painting has been in this direction is a commonplace, but few people understand what this really means, and Mr. Clutton-Brock's book should make the matter clear to the simplest intelligence. It is not enough, for artistic purposes, that a man should know what a tree looks like, or even how to "do" it in terms of drawing or painting; he must know it, as a natural fact, well enough to reduce its representation to terms consistent with the general intention of the work of art as a whole—whether as a linear pattern or as a three-dimensional composition of masses. He must have comprehended the tree intellectually, or, as Emerson said, he must have "been a tree."

Therefore, what looks like a simple matter of accuracy in representation is in reality an extremely complicated business, and Mr. Clutton-Brock has followed its complications, as they were gradually solved in French painting, with remarkable insight and clearness of statement. Disregarding the comparatively simple problem of the technical reduction of the fact, as how to "do" a tree in line, he keeps his eye always on the true artistic reduction, and the result is that his book throws a good deal of light on aspects of French painting that he has deliberately excluded. It is, indeed, a good illustration of the truth that any approach to a subject, which is central in aim and consistently pursued, ends by being an effective substitute for all other possible approaches, and the faithful reader of the book will have learnt a great deal about French painting on the historical and human sides without knowing it.